This article originally appeared in The Modern Leadership Issue of Performance Matters Magazine. To request a print or digital copy of the magazine, click here.

Our client, Alex, was admired as an individual contributor for exceptional results; they took pride in never dropping the ball. This drive to succeed, coupled with the fear of making mistakes, reinforced Alex’s belief that meeting goals and delivering exceptional results depended upon their ability to maintain vigilance and control. Alex feared that if they didn’t personally do the work, it would be subpar. As a high performer, Alex was continually rewarded, validated, and recognized for their exceptional work and ultimately was promoted from individual contributor to people manager.

As a leader, Alex continued to maintain control and oversee every aspect of the team’s work. That seemed to work for a while in their first people management role, but when they became a leader of leaders, balls started to drop. Team frustration mounted—some team members spiraled, losing motivation and disengaging from their work. Others resorted to backchannel communication, complaining about Alex, and attempting to figure out what Alex truly wanted from them. With every ball dropped—a missed deadline, a presentation not hitting the mark—Alex’s internal narrative of “I can’t trust my team to do good work, so I must do more” grew stronger. This in turn reinforced the team’s narrative of “Alex doesn’t trust us to do great work so why even try.”

Alex was in a problem-reacting cycle. Problem-Reacting happens when a leader’s underlying assumptions or beliefs (such as “relying on others is not safe, I can only trust myself”) drives them to act in a way that may temporarily relieve anxiety or fears, but ultimately impedes long-term goals and aspirations. Often, this kind of leader tends to work long hours, doesn’t develop strong trusting relationships with their team members, and eventually burns out. With support, Alex uncovered that their problem-reacting tendencies were rooted in past experiences where people had not come through for them, resulting in loss and hardship.

Alex’s pattern looked like this:

This vicious cycle continued until one quarter when Alex’s team did not achieve team objectives. Alex’s next-level leader stepped in to share their observation that Alex was not successfully leading their team, and suggested that they work together on an improvement plan. Alex reached out to team members via a 360-degree survey for feedback. Although this feedback was initially devastating for Alex, it also opened their eyes to a blind spot; and it prompted a complete reframe.

Receiving feedback was a catalyst for Alex, kickstarting their transformative leadership journey. By uncovering the root causes of their reactive behaviors, Alex gained a deeper self-awareness of their triggers and began challenging limiting assumptions and beliefs. With next-level leader support and that of other mentors and coaches, Alex began by writing down who they aspired to be as a leader. Their leadership mantra became, “I empower, develop, and support team members in service of achieving our team goals,” acting as their north star. Of course, it was not easy to live by this mantra when scary or challenging situations arose. For example, letting go of control felt unsettling and risky. In these instances, Alex relied on their leadership mantra while also tuning into their body and emotions. They began by reflecting on questions that gave them more clarity:

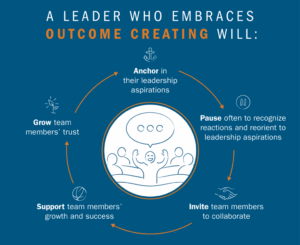

These prompts allowed Alex to recognize the reaction happening within their body, providing a new frame to guide their actions. The team began noticing Alex engaging them in decisions and coaching them to be empowered owners of their work. Over time, Alex experienced their workload begin to distribute and change. Team members were owning more from the start and involving Alex as a thought partner for direction or roadblock clearing. Outcomes skyrocketed. Trust multiplied. As Alex shifted away from a problem-reacting mindset, they entered what we call an outcome-creating or virtuous cycle.

Now Alex’s pattern looks like this:

Moving from problem-reacting to outcome-creating is referred to as adaptive change, taking root in small moments and iterative behaviors over time. It’s the kind of shift that’s transformative, meaning the proverbial rubber band does not snap back. This change becomes a new way of being and brings a new mindset.

While our individual problem-reacting patterns vary, we all have them—from the front line to the C-Suite. Some of us may see a bit of Alex in ourselves, while others may experience slightly different patterns. Here are a couple more patterns that may resonate for you:

Each of these patterns is rooted in different underlying beliefs about ourselves, but the antidote for each is the same: adaptive change. When we pay attention to how we impact others; open ourselves to and seek feedback; pay attention to how we feel and act when we are triggered; and try out new, outcome-creating ways of thinking, feeling, and behaving; then we are doing the hard work that results in adaptive change.

This article originally appeared in The Modern Leadership Issue of Performance Matters Magazine. To request a print or digital copy of the magazine, click here.